These days major debates center around scientific information – from climate change, gene-editing to vaccinations – yet, despite the data-driven nature of science, there are deeply divided opinions regarding these hot topics. For researchers, it might be frustrating to witness scientific findings being misinterpreted or exaggerated. But it’s not surprising that so much science is misunderstood. Too many scientists still reside within their own research bubbles, which is counterproductive.

.jpg?width=6720&name=shutterstock_728227891%20(1).jpg)

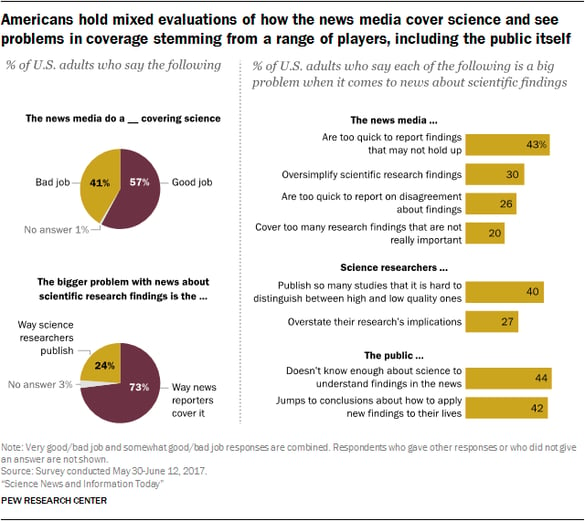

STEM plays a central role in today’s controversies and policy-making. In order to effectively inform the public about matters that are contingent on science, research has to leave the lab. The truth of the matter is that most people don’t seek out scientific information for themselves. According to studies by the Pew Research Center, the majority of Americans only finds scientific news through happen-chance. As we stand, there is

not enough communication between scientists and non-scientists. 54% of Americans get their science information from general news outlets, yet perceptions about the accuracy of this third-party information is mixed.

At the moment, a lot of scientific discovery and news get lost in translation. Information from the lab gets passed to journals then news outlets to influential voices and finally to the public. It’s no surprise that so much becomes manipulated and misinterpreted. The best way to ensure that news is accurate is to skip the middle men and communicate directly with the public.

Effective science communication is not has difficult as it seems. There are simple ways to talk about your work to non-scientists. Here’s how you can get started.

1. Know your audience.

The way you deliver science information should vary based on who you’re speaking to. It seems obvious, but many scientists struggle to talk about their work outside of labs and conferences. However, the way you communicate science is not a one size fits all.

2. Be human.

Probably the most efficient way to seem cold and robotic is to use jargon and numbers. It also does a decent job of losing someone’s attention. Again, know your audience and anticipate what they, whether an individual or a few hundred Twitter followers, knows. There’s no need to use the term “bimodal distribution”, when you can just as easily say that the effect is different between two groups.

3. Be relatable.

In addition to avoiding jargon and numbers, a great way to explain complex concepts is to use analogies or metaphors. Break down ideas and compare them to something that your audience can understand.

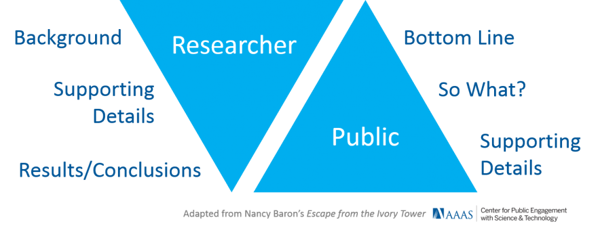

4. Scientists and non-scientists tend to have inverted communication styles.

Scientists are trained to think, write, and present in a way that corresponds with the scientific method. It might be so ingrained that it goes unnoticed, but scientists tend to start off with a lot of background information. The intricacies might be fascinating to some, but to a general public that is not well-versed in the topic, it falls back into jargon territory. Instead, start with the bottom line. What is the message you’re trying to get across? Why does it matter? After you’ve captured your audience’s attention, then proceed with supporting details (in laymen’s terms of course).

5. Use your resources.

Social media has proven itself to be especially valuable for sharing news and opinion, and is used by politicians, influencers, and media outlets alike. Nowadays, an increasing number of scientists have also taken to these channels to share their discoveries, rectify misunderstandings, and to humanize themselves. You can most likely find them under #SciComm on Twitter.

I also want to add that it is becoming easier for scientists to create engaging and visually pleasing materials to explain their work. My personal favorites include Animate Your Science and BioRender.

Remember, the best time for #scicomm is all the time. You don’t need a huge social media following or a designated platform to share your research. No matter what topic you study, you can share it with friends, family, and willing strangers. Even if your research question doesn't seem relevant to current events, the mere act of connecting to non-scientists and humanizing the people behind STEM is important in and of itself.

.jpg)