As we head out of February and into March, we celebrated the resilience of our colleagues from diverse backgrounds during Black History Month and continue to promote the accessibility to science and STEM careers. There were a couple really important dates to recognize girls and women in February as well, with the National Girls & Women in Sports Day on the first day of the month, followed by the International Day of Women and Girls in Science on February 11. And now in March, we have the entire month to celebrate the contributions of women throughout our history. To kick off Women's History Month, I wanted to take a look at some of the most accomplished women scientists that advanced our knowledge to new heights while overcoming societal pressures and prejudice.

As we head out of February and into March, we celebrated the resilience of our colleagues from diverse backgrounds during Black History Month and continue to promote the accessibility to science and STEM careers. There were a couple really important dates to recognize girls and women in February as well, with the National Girls & Women in Sports Day on the first day of the month, followed by the International Day of Women and Girls in Science on February 11. And now in March, we have the entire month to celebrate the contributions of women throughout our history. To kick off Women's History Month, I wanted to take a look at some of the most accomplished women scientists that advanced our knowledge to new heights while overcoming societal pressures and prejudice.

National Women's History Month

Originating from a series of Congressional proclamations in the 1980s, the National Women's History Month in the United States celebrates the contributions that women have made to the country and recognizes the specific achievements women have made over the course of American history in many different fields, including the sciences. In my experiences, in addition to encouraging girls to try out for the baseball team rather than being relegated to softball, I also helped my female students find and enter into research opportunities at university laboratories over the summer as well as other outreach programs. I believe strongly in the power of women to enact change for the greater good, from my many teachers and mentors who just happened to be women, including my thesis committee chair, and my various supervisors as I transitioned into industry, and it is refreshing to see women take a larger role in the academic sciences as well.

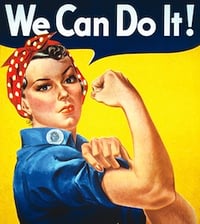

Despite the progress made over the decades to allow more women to participate and thrive in the science fields, the proportion of women still lags far behind men in STEM occupations. As of 2019, the United States Census Bureau presented data showing that although women now make up nearly half of the American workforce, they only make up less than a third of all STEM workers. Part of the idea behind awareness events like Women's History Month is to encourage more girls and women to realize that their potential is boundless and they can do anything they set their minds on. The other part is to encourage allies in a position of authority and leadership to continue opening opportunities up for girls and women and put them in the best position to succeed.

Despite the progress made over the decades to allow more women to participate and thrive in the science fields, the proportion of women still lags far behind men in STEM occupations. As of 2019, the United States Census Bureau presented data showing that although women now make up nearly half of the American workforce, they only make up less than a third of all STEM workers. Part of the idea behind awareness events like Women's History Month is to encourage more girls and women to realize that their potential is boundless and they can do anything they set their minds on. The other part is to encourage allies in a position of authority and leadership to continue opening opportunities up for girls and women and put them in the best position to succeed.

Recognizing Women in Science

The cream of the crop of the scientific community is recognized annually by the Nobel Prize, which was established in 1901. Over a century after its inception, there have been 615 Nobel Prizes awarded to 989 recipients, including 30 organizations including the Red Cross and also counting multiple award winners. Of these winners, only 61 Nobel Prizes were awarded to women, and of this tiny proportion, only 23 won in the science categories, which includes the two prizes won by Marie Curie.

The folks at Wikipedia have compiled the list of all female Nobel laureates, and with the dates of each prize, you can see the huge droughts in between each award to a woman, although the gap has noticeably shrunk in recent years with women cleaning up in the physics and chemistry categories over the past five years. You have to wonder about some of these gaps, given the contributions of women like Hedy Lamarr (shown to the right), without whom we might have experienced at least some delays in the wireless internet and Bluetooth technologies we take for granted today. Others, like Rosalind Franklin, sadly died before they would have been rightfully recognized for their critical contribution to a discovery, in this case the structure of DNA. And even in the old days when men may have scoffed with a woman in the lab, some of them obviously existed in a lab setting and contributed to the discoveries that led to other Nobel Prizes, even if they didn't happen to be the corresponding author on the seminal paper.

The folks at Wikipedia have compiled the list of all female Nobel laureates, and with the dates of each prize, you can see the huge droughts in between each award to a woman, although the gap has noticeably shrunk in recent years with women cleaning up in the physics and chemistry categories over the past five years. You have to wonder about some of these gaps, given the contributions of women like Hedy Lamarr (shown to the right), without whom we might have experienced at least some delays in the wireless internet and Bluetooth technologies we take for granted today. Others, like Rosalind Franklin, sadly died before they would have been rightfully recognized for their critical contribution to a discovery, in this case the structure of DNA. And even in the old days when men may have scoffed with a woman in the lab, some of them obviously existed in a lab setting and contributed to the discoveries that led to other Nobel Prizes, even if they didn't happen to be the corresponding author on the seminal paper.

The gap of 60 years between Marie Curie's first prize and Maria Goppert Mayer's prize in the physics category is particularly glaring, almost saying that women did nothing worthy of recognition which is far from the case! Over 120 years, having only 12 women in the physiology or medicine category, four in physics, and eight in chemistry (again including both Curie's prizes in physics and chemistry) is insultingly low, and despite the recent uptick, women still lag far behind in recognition at this highest level. I have thankfully seen many women scientists being lauded as leaders in their chosen field, and perhaps some of them will join the pantheon of scientific immortals in due time as the gender gap continues to shrink. In the meantime, let's take a look at some of the women the Nobel committee did recognize.

The Center of Attention

The most recent physics Nobel laureate who happened to be a woman, Andrea Ghez, was recognized because of her efforts in developing new telescope technology and techniques to explore the center of our Milky Way galaxy and provide evidence that it is home to a supermassive black hole. Using (probably) a lot of math I don't understand, they mapped the orbits of the stars closest to the center of the galaxy and observed a swirling effect, suggesting the presence of something invisible but massive that was causing that swirling. These days, in popular science communication and in science fiction, we take the supermassive black hole theory for granted and some even tout it as fact given the currently accepted theory, but it required decades of observation and calculation by dedicated scientists like Andrea Ghez, and this award was justly deserved and just a couple years after another woman won the physics Nobel Prize!

The most recent physics Nobel laureate who happened to be a woman, Andrea Ghez, was recognized because of her efforts in developing new telescope technology and techniques to explore the center of our Milky Way galaxy and provide evidence that it is home to a supermassive black hole. Using (probably) a lot of math I don't understand, they mapped the orbits of the stars closest to the center of the galaxy and observed a swirling effect, suggesting the presence of something invisible but massive that was causing that swirling. These days, in popular science communication and in science fiction, we take the supermassive black hole theory for granted and some even tout it as fact given the currently accepted theory, but it required decades of observation and calculation by dedicated scientists like Andrea Ghez, and this award was justly deserved and just a couple years after another woman won the physics Nobel Prize!

The Acceleration of Genetic Study

With the rarity of women winning science Nobel Prizes, it is even more rare for them to win solo, as many of them share their prizes which emphasizes the idea that science is a global collaboration after all. So it is noteworthy when two women are the only recipients of that year's chemistry prize, as Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier were recognized for their discovery and characterization of CRISPR gene editing. Now, over a decade since the first publications on the phenomenon, CRISPR has accelerated genetic research and the hopes that one day, the technology can be refined enough for targeted gene therapy the likes of which we might only have dreamed about or seen on Star Trek. The fact that these brilliant women were awarded so soon after their discovery shows how impactful it was for not just science, but for all of society.

A Lesson in Perseverance

I first learned about transposons in college and it helped explain why, for example, so many common folds and motifs like the immunoglobulin fold or the Src-homology 2 domain were repeated over and over in evolution. When you dig into the history behind transposable elements, you get to read about the life and efforts of Barbara McClintock, who won the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine decades after her initial proposals and characterizations of mobile genetic elements. Imagine making your first discoveries in the 1940s and showing mounting evidence for your proposal through the 1950s, but then being shouted down by your contemporaries and then discouraged from continuing to publish. It turns out that McClintock was just light years ahead of everyone else, as her work was corroborated in the ensuing decades and she was ultimately recognized as the true pioneer of the field by later researchers, culminating in the Nobel Prize, and becoming the first woman to win the physiology or medicine award solo.

Always Moving Forward

We still have a long way to go to achieve true gender equality, but as I look at the accomplishments of many of my female mentors, classmates, and associates, I see excellent examples of what dedication, ingenuity, and opportunities will do to cultivate a great mind. The women in our history and the women we work with now show the next generation of girls that STEM is a viable option. With support from all of us, we can encourage young girls to pursue their passions without feeling the limitations that society can put on women as we transition to a more accepting and accessible future.