If you are reading this, either having earned your first faculty position or about to embark on leading a huge project, congratulations! You have obviously demonstrated the creative problem solving and other skills needed to successfully carry out and complete a scientific study…but maybe you’re not confident in your ability to lead or mentor? I would argue that many experiences you have accumulated up to this point will help you become the best mentor you can be, so let’s get to it as you cultivate the next generation of great researchers!

If you are reading this, either having earned your first faculty position or about to embark on leading a huge project, congratulations! You have obviously demonstrated the creative problem solving and other skills needed to successfully carry out and complete a scientific study…but maybe you’re not confident in your ability to lead or mentor? I would argue that many experiences you have accumulated up to this point will help you become the best mentor you can be, so let’s get to it as you cultivate the next generation of great researchers!

I wrote this mostly with academic lead investigators in mind, but communication and empathy are key to any enterprise, so I hope you find this post useful regardless of where you are coming from.

A Trickle-Down Attitude

Just as children mimic the behaviors and preferences of their parents, to a lesser extent, so too will your new graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and support staff. You may ask yourself, then, “What kind of standard and example do I want to set for the people under my supervision?” You do want to be true to yourself and your values, but also recognize that your leadership style will trickle down to the next generation and probably beyond, so you may have to evaluate which of those values to accentuate, while moving others to the lower priority list.

Just as children mimic the behaviors and preferences of their parents, to a lesser extent, so too will your new graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and support staff. You may ask yourself, then, “What kind of standard and example do I want to set for the people under my supervision?” You do want to be true to yourself and your values, but also recognize that your leadership style will trickle down to the next generation and probably beyond, so you may have to evaluate which of those values to accentuate, while moving others to the lower priority list.

When I think of a good mentor, I imagine someone who is accessible and amiable. A good mentor should have good communication skills, empathy, and flexibility. At the same time, a good mentor will reasonably hold the students accountable to a justifiable standard while giving them enough room to grow freely as their abilities allow.

Do Unto Others

It’s easier to walk a mile in the shoes of your trainees since you were there not too long ago. The long hours, the ludicrously high rate of failure, the stress of trying to find funding while working towards that big publication and thesis—all of that is intimately familiar. It’s almost a huge set of experiences you would not wish upon anyone, even if it does “build character”! Unfortunately, that is the system we work with, and aspiring scientists must suffer through some form of it to get that PhD. So how would you go about making life more bearable for those who look to you for guidance?

Because these are people, real human beings who will be working with you for years, they deserve respect and empathy even if you are their superior. Some will come fresh out of college with their eyes on the Nobel Prize years from now, while others have weathered many real-life experiences and bring family and other considerations with them. I truly believe my experiences as a tutor, a laboratory mentor, and a teacher have helped me in developing compassion and rapport with people coming from diverse backgrounds. It also has taught me that not everyone is like me, nor have they experienced the same things, and by extension, they will not be exactly like you, so it is important to give them some space and freedom to grow as individuals and as scientists. Similarly, it is important to vet new personnel carefully to ensure that they are compatible with existing lab folks, both in ability as well as in personality. This doesn’t mean you’ll never have lab arguments, but it’s usually a good idea to do everything possible to minimize those situations.

Because these are people, real human beings who will be working with you for years, they deserve respect and empathy even if you are their superior. Some will come fresh out of college with their eyes on the Nobel Prize years from now, while others have weathered many real-life experiences and bring family and other considerations with them. I truly believe my experiences as a tutor, a laboratory mentor, and a teacher have helped me in developing compassion and rapport with people coming from diverse backgrounds. It also has taught me that not everyone is like me, nor have they experienced the same things, and by extension, they will not be exactly like you, so it is important to give them some space and freedom to grow as individuals and as scientists. Similarly, it is important to vet new personnel carefully to ensure that they are compatible with existing lab folks, both in ability as well as in personality. This doesn’t mean you’ll never have lab arguments, but it’s usually a good idea to do everything possible to minimize those situations.

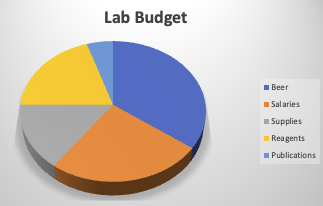

You will find your own groove with the folks who choose to work with you, but I think the best thing you can do is to set reasonable standards, understand that your trainees have needs in balancing their research work and their lives, and to be a friendly advocate and a good listener when they need it. It might be a good idea to buy the lab some beer and a meal here and there, too!

Those Who Can Do, Also Teach

In addition to your responsibilities to teach certain courses if you are in academia, you are responsible for training your crew in how to be a good scientist and solve problems. This necessitates effective communication skills, which doesn’t just involve telling someone how to do something, but also how you deliver the message and how you help them start learning to think for themselves so that someday, they won’t need you anymore (but they’ll hopefully call and say hello).

Part of communication is being crystal clear about what tasks are expected of each trainee, how they can collaborate with each other to achieve major projects, and the steps they will need to take to complete the tasks. While your responsibilities may have shifted away from the lab so you can write grants and papers, you still have the experience of many years of bench work that can be passed to your students and postdocs, some of whom might not be as familiar with those protocols. You also have an opportunity to help your trainees improve their organization and time management skills, through activities such as lab clean-up, data presentations, and preparations for seminars and conferences. Your time (both in and out of lab) is important, and so is theirs, so let’s not waste it!

Part of communication is being crystal clear about what tasks are expected of each trainee, how they can collaborate with each other to achieve major projects, and the steps they will need to take to complete the tasks. While your responsibilities may have shifted away from the lab so you can write grants and papers, you still have the experience of many years of bench work that can be passed to your students and postdocs, some of whom might not be as familiar with those protocols. You also have an opportunity to help your trainees improve their organization and time management skills, through activities such as lab clean-up, data presentations, and preparations for seminars and conferences. Your time (both in and out of lab) is important, and so is theirs, so let’s not waste it!

At the same time, because you’re now at that slope in the Dunning-Kruger curve that comes with the experience of knowing you don’t know everything, you can also admire that someone can and will bring in new skills and knowledge to supplement your own. Fostering a collaborative and positive teaching environment is beneficial to the collective. Along with the new skills and knowledge, the doctrines of mutual respect plus the love of teaching will also pass on to new labs and organizations as folks come and go.

Allocating Resources

Graduate student stipends and postdoc salaries are capped (perhaps unfairly, and unfortunately there’s not much you can do about it for now), so they are going to try to finish their work and get to their next destination as quickly as possible. With the evolving job market and the ivory tower of academia losing some of its shine, you’ve had to overcome numerous obstacles to recruit and ensure your qualified trainees that they can expect a reasonable time frame. Before we even get into your budget (with funding opportunities scarce and the cost of research rising), you want to sustain your lab community’s passion for science and to help them persist, particularly those who weren’t born with a silver spoon. Having established good habits and developed rapport with your staff as we discussed above, let’s now work on making sure the projects can get done, while keeping the passion for discovery alive, with time and funding to spare.

While some in the lab may think of you as Scrooge McDuck (this graphic was funny when I was in grad school, but I don’t think parts of it aged very well), funds are finite and salaries are expensive. This means restrictions on the number of people who can be in the lab and the quantity of reagents and equipment you can procure to complete your research. We already talked about optimizing workspace organization, which can save time, improve comfort, and reduce waste, which will be a huge savings from the start. There are also lab hacks that you can think up on your own or find via the internet to further streamline workflow and save money and resources.

While some in the lab may think of you as Scrooge McDuck (this graphic was funny when I was in grad school, but I don’t think parts of it aged very well), funds are finite and salaries are expensive. This means restrictions on the number of people who can be in the lab and the quantity of reagents and equipment you can procure to complete your research. We already talked about optimizing workspace organization, which can save time, improve comfort, and reduce waste, which will be a huge savings from the start. There are also lab hacks that you can think up on your own or find via the internet to further streamline workflow and save money and resources.

With many different personalities and styles milling about, time management is key, and the monumental challenge lies in organizing schedules and collaborations while respecting work-life balance and maintaining reasonable workloads. But if you invest the time to get to know and value the people in your care, the work will take care of itself because the people are already taken care of. It’s a lot easier to get people to buy in to your system if they already like you!

Preparing For Persistence

As you are aware, the road from matriculation to the successful thesis defense is a long and arduous path, fraught with peril and obstacles (almost like a Dungeons and Dragons campaign, but probably slightly less fun with much higher stakes). Because your trainees are obviously highly skilled and intelligent people, and they are motivated to generate scientific discoveries for the benefit of all humanity, one of the things you need to do is to provide a positive working environment and maintain that level of motivation.

It is true that the PhD process is full of positives in terms of skills acquisition, collaboration, and the immersion into knowledge. However, the artificially capped pay (even with most PhD bioscience programs having fully funded tuition) can make it stressful for your trainees, and the existing training structure (I went through it too!) is a huge source of the negativity that you might notice on social media from graduate students and postdocs. You may not have direct say in improving compensation, but you can impact their experiences while working with you, and perhaps one day, that will contribute to a systemic overhaul that enhances the PhD experience for the better. People work better when they're not miserable, and are more likely to persist through to graduation if they can feel rewarded more often than not, even in the face of experimental failures. That is something you definitely can control!

We found this Twitter thread (about how to adjust your life as a new mentor so you can become a great mentor) super-helpful as well if you wish to check it out:

Hey, new faculty!! Congrats on your new jobs. If you'd find it helpful, I've made a list of the stuff that's made my life a lot easier in this chaos job. I can't promise I know what I'm doing myself, but I hope these might help you as you adjust! 1/probably too many

— Dr. Sarah Sheffield (@sarahlsheffield) July 31, 2022

Best of luck in your research goals, and best wishes for you and everybody working with you!