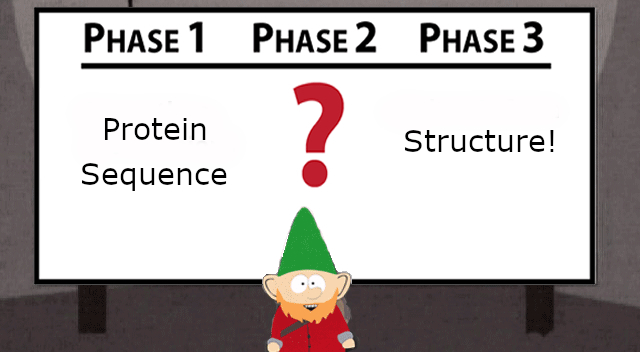

In the wake of new programs that produce artwork derived from existing media, ChatGPT, and even algorithms that can predict protein folding, it is evident that the age of artificial intelligence (AI) is upon us. In many cases, the AI programs and tools are far more advanced than we have previously seen, to the point where humanity can derive great benefit from AI while fearing how it may affect our society and livelihoods. While it is unlikely that we will be subjugated by our new robot overlords, it is still important to explore what has been done and remains possible through AI, and our considerations for its ethical usage.

My first experience in a basic research laboratory was a structural biology project, in which we were attempting to solve the structure of a nervous system protein known as myelin basic protein (MBP). As a rookie undergraduate scientist at the University of California, I had great mentors who taught me everything, from how to purify recombinant proteins from bacteria to doing library work to understand what had been done before so I could build upon it. I also learned how to use an electron microscope (EM) to gather structural data. MBP was an interesting challenge as it had multiple isoforms due to alternative splicing, and generally behaved like a random coil. 1 The major function of MBP is to take advantage of its highly positive charge to compact myelin in higher organisms, with research over the years suggesting it may have some capacity to form alpha helices, although atomic-resolution structures have not yet been reported. MBP has also been reported as a biomarker in autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis. 1